French President Emmanuel Macron has flown to the Pacific island of New Caledonia in a bid to help quell fierce rioting there. The French overseas territory has seen a surge in violence by the indigenous Kanak people, who have been enraged by the decision of Paris lawmakers to give French residents a greater say in local elections. It is the latest blunder by the Macron government as it seeks to keep control of this latter-day colony.

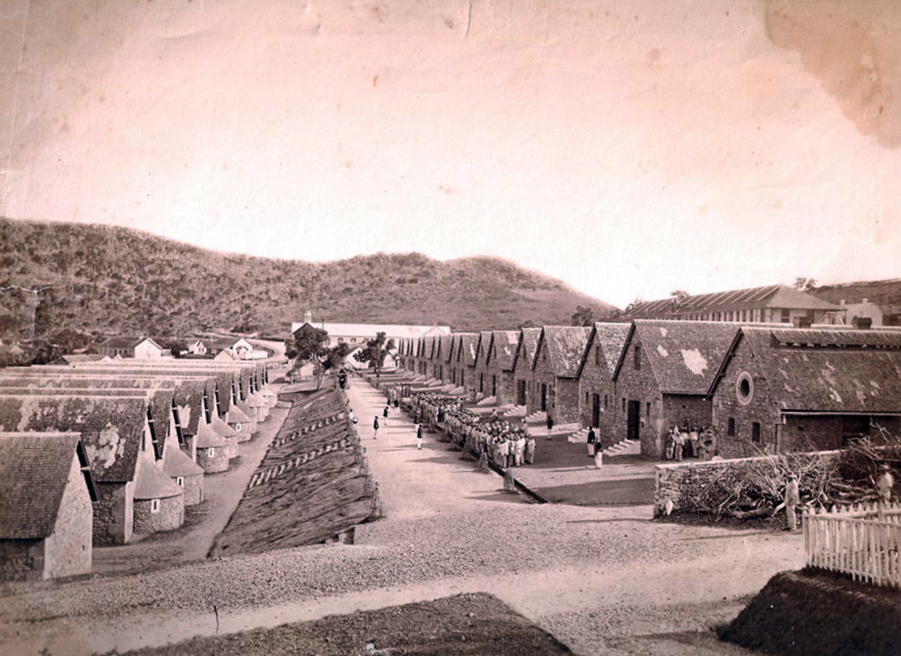

With an Austronesian presence dating back as far as 2000 BCE, New Caledonia was a late discovery of the European explorers. James Cook visited in 1774, paving the way for a variety of traders and navigators in the late-18th and early-19th centuries. The islands were occupied by France in 1853, which established a penal colony there in 1864. This lasted for thirty years and was the destination for many political prisoners, as well as criminals.

The discovery of vast nickel deposits reinforced French interest in New Caledonia, though encouraging immigrants from the old country was difficult. The Kanak were excluded from the colonial colony, confined to reservations whilst being decimated by European-introduced diseases. An uprising in the late 1870s caused over two-hundred French deaths, but was repulsed, with a further rebellion in 1917 also short-lived.

Loyal to the Free French despite the decades of colonial exploitation, New Caledonia served as an important Allied base in World War Two, particularly for the US Navy. It became an overseas territory of France in 1946 and all its residents were granted French citizenship. With nickel production ramping up, and a ready-made market in Australia, internal tensions eased, with the Kanaks becoming a minority in comparison to Europeans and other Polynesian groups.

By the late 1970s, however, the Kanaks were fed-up with their disregarded status. ‘Les Événements (The Events) erupted in an outbreak of street violence directed against the European political leaders of the islands. Disorder spread into the early 1980s, drawing concessions from the Socialist government in Paris, which initially offered the Kanaks sovereignty. This plan disintegrated in 1985 amidst further violence and the election of a nationalist government in France in 1986 which involved reprisals against the Kanaks, including allocating away some of their land.

Increased efforts by French gendarmes to quell the resistance, led to a hostage crisis, with 27 police officers taken prisoner in a cave by Kanak independence advocates. The ensuing military rescue ended in bloodshed. An agreement in 1988 halted the violence and after a decade of conciliation talks, the Nouméa Accord was signed in 1998. Allowing for greater self-governance for the Kanaks, the Accord also promised a decision on New Caledonia’s long-term future, setting provisions for up to three independence referendums.

The first referendum took place in 2018, with 56.7% of eligible voters casting their ballot in favour of remaining an overseas territory of France. A 2020 referendum drew the same outcome, albeit with a reduced majority of 53.3%. The third referendum took place in 2021 and promised to be a cliffhanger. However, having requested that the vote be delayed to let the Kanaks to recover from the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, the French government authorised it to go ahead on schedule. The Kanaks boycotted the referendum and 96.5% of those who voted declined independence.

Tensions have been on a knife-edge ever since and with the Kanaks now comprising a majority of the demographic (approximately 41%), any future referendum would be likely to champion independence. That is where the recent law from Paris comes in. It basically relaxes the eligibility criteria for voters in future elections and referendums, with the electoral roll previously reserved for those with long-standing ties to New Caledonia. This was a provision of the Nouméa Accord. The Kanaks fear that Europeans with more recent residency in New Caledonia will swamp the vote, ending for good the prospects of independence.

It is a clumsy move by France, one continued without allowing a proper debate in the territory the law most affects. Having failed to alleviate the troubles of West Africa despite frequent meddling, the French have not learnt that their neo-colonial ventures are unlikely to succeed in the 21st century. Deploying additional police and military forces to New Caledonia may win the street battles, but not hearts and minds.

Without a deliberate attempt to upset the population balance, the French will need to bow to the inevitable and accept independence for the Kanaks and New Caledonia. Frustratingly, the Paris government could have managed such a transition peacefully and openly by engaging in dialogue, with a clear roadmap to sovereignty. Yet, its inability to eradicate an outdated mindset, and its refusal to have ever taken the Kanak seriously, means the road to independence will likely now be rocky and abrupt, potentially undermining the foundations of whatever fledgling state emerges.