Between the 5th and 12th September 1914 the First Battle of the Marne was fought between French (with British support) and German troops to the east of Paris. Casualties across both sides totalled more than 500,000. Having enacted the Schlieffen Plan to advance through neutral Belgium and invade France in August, the battle marked the end of Germany’s ambitions to secure a 40-day conquest over its neighbour. Over the next four years, a bloody war of attrition would be fought across what came to be known as the Western Front, a hopeless stalemate which resulted in millions being slaughtered.

Whilst the Russo-Ukrainian War is incomparable in scope to World War One (WWI), a similar stalemate has set in with no obvious prospect of it being broken on the battlefield. Having halted, and in some areas pushed back, Moscow’s initial invasion forces, the Ukrainian counter-offensive has struggled to advance, whilst Russia’s offensive efforts have been characterised by military failures and appalling morale. Estimates on the number of dead and injured vary wildly, but as of August 2023 US officials calculated almost 500,000 casualties amongst the armed forces of Russia and Ukraine. Over 11,000 Ukrainian civilians have been killed.

Although the war has witnessed the deployment of modern technology such as drones, hypersonic missiles and artificial intelligence, the battlefield is characterised by a form of warfare not too dissimilar to WWI. Trench systems, artillery barrages, gun battles, tank advances. The same tactics deployed to insufficient affect over a century ago remain a staple of this twenty-first century conflict. It is turgid, bloody fighting, each side testing the other’s resolve, defensive lines easier to hold than to break.

WWI dragged on because of the refusal of political and military leaders to compromise. Whilst some may have chosen to remain oblivious to the carnage, most were aware and yet chose to do nothing, or failed to impose their will. What by the end of 1914 was an evident fact – that the stalemate on the Western Front would hold despite the millions of bodies and tonnes of ammunition each side was throwing at one another – did nothing to bring about a ceasefire. This is not particularly surprising, for both the Central Powers and Allied Powers had very different ambitions, and very different standpoints on who had provoked the war. Compromise could not easily be sold to populations forced into war and the more men that were sent off to die, the harder it became to justify anything other than absolute victory.

Russia and Ukraine are approaching a similar situation, if they have not already reached it. Vladimir Putin has justified the war both to himself and the Russian people as one of historical destiny, a rightful unification of a homogenous group of people. His failure to win a quick victory means that any negotiation to conclude the conflict without the affirmation of meaningful territorial gains for Russia would be a humiliation. For Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, nothing but the complete removal of Russian forces from his country – including the Crimea which was annexed in 2014 – is palatable.

Zelensky is in a difficult situation. The war has been fought exclusively on Ukrainian land, has devastated the country’s economy and resulted in thousands of civilian casualties. To maintain the stalemate – let alone succeed with his counter-offensive – means continually convincing his European and American allies to financially support the Ukrainian war effort, however unpopular it may be in the host countries. Each month that goes by the suffering of his people increases, with no end in sight. Putin, meanwhile, having retained domestic and a large degree of international support, can afford to wait.

The French, with their British allies, were like the Ukrainians fighting to evict an invading force from their territory. The Germans, meanwhile, were driven by a sense of historical destiny and a political-military hierarchy with delusions of grandeur, much like Russia today. Retreat would have been unthinkable despite the decimation of the nation’s youth.

It took the American entry into the war in 1917 for the tide to turn against Germany on the Western Front. Still, the fighting dragged on and the Germans launched a final desperate offensive in the Second Battle of the Marne in July 1918. Its failure and subsequent Allied advance ultimately convinced the country’s leaders to sue for peace.

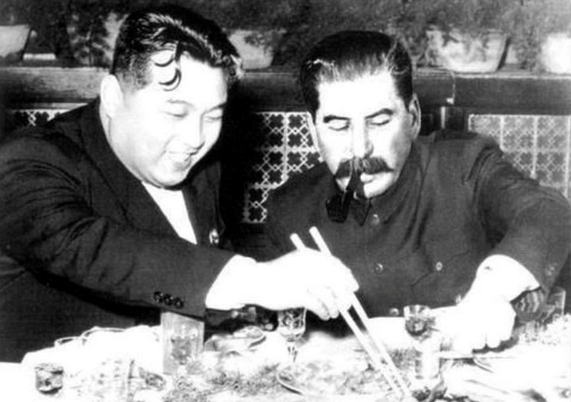

For a decisive break in the Russo-Ukrainian War, either Russia’s major international ally China would have to throw its weight behind Kyiv, or the USA – perhaps under a Republican presidency – would have to abandon the Ukrainian cause. With neither prospect in immediate sight, the stalemate will persist.

Despite the disturbing parallels from history, life will continue to be sacrificed until a seismic rupture in proceedings can be enacted.