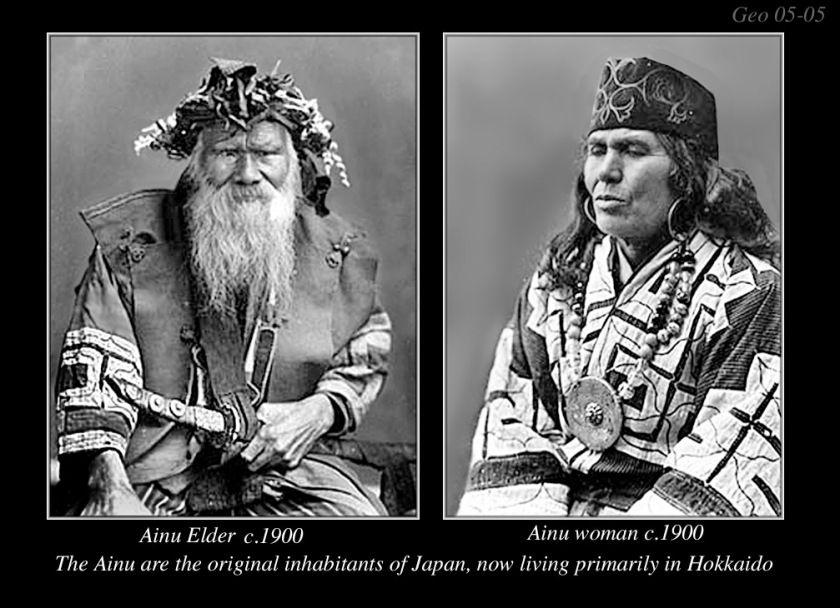

In the midst of the reporting on the tragic landslides that have killed upwards of 30 people in Hiroshima Prefecture, an item of periodic contention on the Japanese agenda has been somewhat overlooked: the recognition of the Ainu.

The Ainu claim to be the true indigenous people of Japan. Indeed, their hirsute, Caucasian nature is somewhat at odds with the Japanese. As Neill James wrote during a trip through Hokkaido in 1942:

I was impatient to meet the mysterious Ainu – a primitive uncultured race as hairy as Esau – who for unnumbered centuries had hunted in the tangled jungles of Hokkaido. (Refsing, p.41)

As James quickly acknowledged, this stereotype was completely unfounded yet there is an element of truth in the report when examining the physical comparison between the Ainu and the Japanese, a ‘Mongolian race, smaller in stature, with the typical Mongolian features of the fold in the eyelid, a yellow tinge in pigmentation, black hair…high cheekbones’ etc. (Morton & Olenik, p.4)

After the Japanese arrival, the Ainu were gradually forced to retreat further north until they occupied only segments of Hokkaido, the northernmost of Japan’s main islands. Persistent rebellion was only really brought to an end during the Early Heian Period (794-857) when the Japanese sought to exploit the fertile land of the north, consequently overrunning Ainu territory.

The Ainu were only officially recognised as the indigenous people of Japan in 2008, having been referred to as”kyu-dojin” (uncivilised aborigines) during the century before. However, in a tweet on the 11th August, Yasuyuki Kaneko, a politician based in Sapporo (Hokkaido’s largest city) claimed that ‘there are no such people as the Ainu anymore’.

Whilst undoubtedly an incendiary and insensitive comment, there has always been debate over whether any ethnic survivors of long-subjected tribes ‘truly’ exist. For instance, the Ancient Britons splintered into a plethora of groups, notably Cornish, Welsh and Breton, after conquest by Germanic invaders and the Vikings. Whilst these groups live on in terms of their heritage, culture and language, their physiological uniqueness (in that they are an inherently different people) is debatable. Indeed, one of the historic characteristics of conquest is the interbreeding of the conquered and the subjected, a way of ensuring the acquiescence of the latter and supremacy of the former.

The Ainu, as with Australian Aborigines, are similarly placed. Are they extinct in theory but preserved by heritage? What defines and makes an ethnic group? Is there a catch-all definition?

It is certainly a topic worthy of debate, for it is an issue facing all so-called ‘indigenous groups’ and ‘ethnic minorities’ desperate to prove and retain their status. At a minimum we must respect diversity and, like the global citizens that we are, ensure our chosen group refrains from trumpeting its superiority over any other, no matter what size or faith.

Sources

James, N. ‘Petticoat Vagabond in Ainu Land and Up and Down Eastern Asia‘ in Refsing, K. Early European Writings on Ainu Culture (2000)

Scott Morton, W. & Kenneth Olenik, J. Japan: Its History and Culture (2005)